Clean architecture is the latest book by Uncle Bob. It defines architectural patterns to make software easy to change. In this blog post, I will go through the book summarizing the main concepts and giving my opinion on it.

Here is the table of contents:

- Introduction

- Code design principles (SOLID)

- Components principles

- Architecture principles

- What’s more in the book

- My opinion and review

Introduction

What is architecture?

Architecture is the shape of a system. Architecture supports the behavior of the system while keeping its flexibility to change. The responsibility for this flexibility is upon the architect and the developers of the system.

What is Clean architecture?

Clean architecture is an architecture following Uncle Bob’s principles. The key idea is to use the dependency inversion principle to place boundaries between high-level components and low-level components. This creates a “plug-in architecture” that keeps the system flexible and maintainable.

Code design principles (SOLID)

A clean architecture starts from clean code. Classes must be clean for components to be clean. Components must be clean for systems to be clean.

Clean code follows SOLID principles. These are guidelines to write focused, extensible and maintainable methods and classes. They are important to architecture but not the focus of the book so I’m just going to state them briefly.

Let me know in the comments if you want a deeper analysis of the SOLID principles or a review of Clean Code.

Here are the SOLID principles:

- Single responsibility principle: a class should have one, and only one, reason to change. Or the new version: a module should be responsible to one, and only one, actor.

- Open-closed principle: a class should be open for extension but closed for modification.

- Liskov’s substitution principle: objects in a program should be replaceable with instances of their subtypes without altering the correctness of that program.

- Interface segregation principle: many client-specific interfaces are better than one general-purpose interface.

- Dependency inversion principle: one should depend upon abstractions, not concretions.

Component principles

Components are the smallest entities that can be deployed as part of a system, for example jar or DLL files. Clean architecture suggests six principles to design components. The former three are about component cohesion, i.e. how to group classes together. The latter three are about component coupling, i.e. how to deal with relationships among components.

The principles on component cohesion are:

- Reuse/release equivalence principle: classes and modules (i.e. a component) reused together should be released together. They should have the same version number and there should be proper documentation such as changelogs.

- Common closure principle: classes that change together should be grouped together, and vice versa. The single responsibility principle at component-level.

- Common reuse principle: don’t force users of a component to depend on things they don’t need. The interface segregation principle at component-level.

A project will follow these principles to different extents, depending on its maturity. In the early stages, developability is more important so the focus should be more on the common closure principle. In the later stages, the focus will shift towards reusability and maintainability, and the reuse/release equivalence principles will gain more importance.

The next set of principles deals with component coupling:

- Acyclic dependencies principle: no cycle in the dependency graph. Cycles couple components and, among other things, force them to be to released together. Use the dependency inversion principle to break cycles.

- The stable dependency principle: less stable components should depend on more stable components. Depend in the direction of stability.

- Stable abstractions principle: stable components should be abstract, and vice versa. An example of an abstract stable component is a high-level policy which is changed by extension following the open-closed principle.

Stability has a precise meaning here: a component is the more stable the fewer outgoing dependencies it has relative to the total of its outgoing and incoming dependencies. We can define a formal metric:

- Stability = (number of outgoing dependencies) / (number of total incoming and outgoing dependencies)

For example, a component with zero outgoing dependencies is maximally stable. This makes it a good candidate to be depended upon because no other components can force it to change. The stable dependency principle says that the stability metric should increase if you move from one component to its outgoing dependencies.

Also, abstraction has a precise meaning here: a component is the more abstract the more abstract classes and interfaces it has relative to the total number of classes and interfaces. Formally:

- Abstractness = (number of abstract classes and interfaces) / (number of total classes and interfaces)

The stable abstraction principle says that a stable component should be abstract. In this way, we can keep it stable and change it at the same time by extension. On the other hand, an unstable component can be concrete because changing it doesn’t impact many components.

For any project, we can plot these two metrics in a scatter plot. The ideal situation is that most components fall in the “main sequence” zone in the following graph:

Monitoring how distant a component is from the “main sequence”, we can detect decreases in software quality. You can find additional examples and details in Clean architecture.

(Keep in mind that Uncle Bob talks in terms of “instability” instead of stability, so formulas and graphs are modified accordingly)

Architecture principles

Architecture is the shape of a system. It includes the system’s division into components, the arrangement of those components, and the ways those components communicate with each other. The purpose of architecture is to facilitate the development, deployment, operation, and maintenance of the system, leaving as many options open as possible, for as long as possible.

Therefore architecture should not only support behavior but also provide flexibility in the life cycle of the system. This is achieved setting boundaries that, firstly, maintain a clear separation between high-level policies and details and, secondly, allow layers to be developed and deployed independently.

Setting boundaries

Boundaries are lines that separate software elements. They separate things that matter from things that don’t, i.e. high-level components from low-level components. If a high-level component depends on a low-level component at the source level, changes in the low-level components will spread to the high-level component. Therefore, we place a boundary between the two, using polymorphism to invert the logic flow. This is the dependency inversion principle in the SOLID principles.

For example, let’s say your business rules depend on a concrete class accessing the database. You want to draw a boundary between the business rules and the database. The first thing to do is to define a new interface representing the database in the business rules component. Then, have your business rules depend on the interface instead of the concrete database class. Then, have the concrete database class implement your interface. The wiring between the database interface and implementation will be done in your main method manually or by some dependency injection framework.

In this way, we made the database a plug-in of our business rules. That is, we can change our database, a low-level component, without affecting our business rules, a high-level component. Uncle Bob believes all low-level components should be plug-ins, for example, the GUI, I/O, web frameworks, etc. This leads to the concept of plug-in architecture.

Separating layers (Clean Architecture)

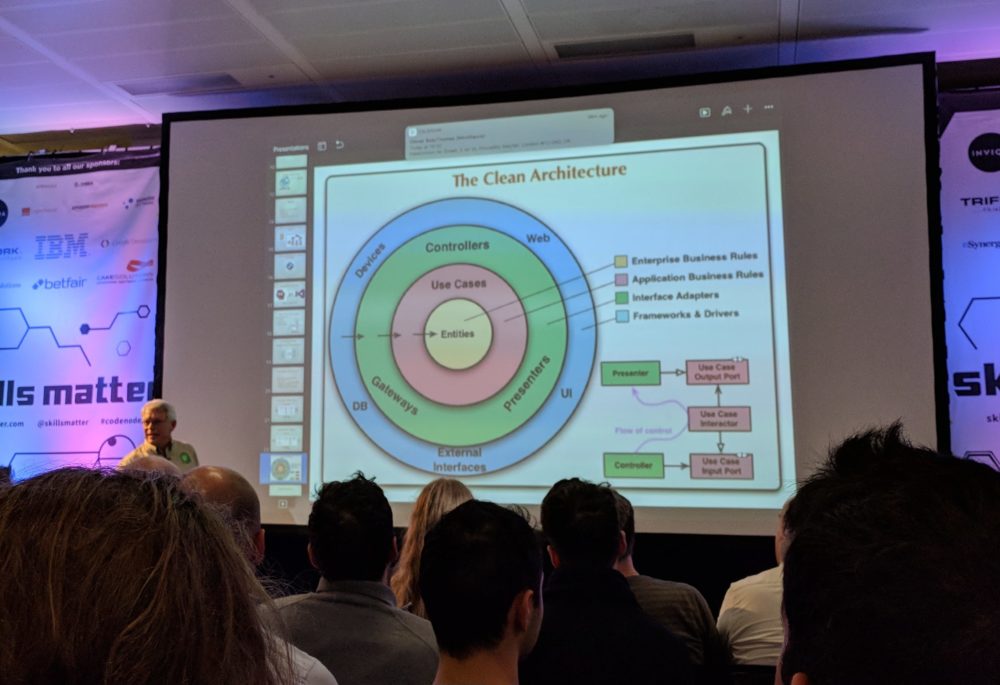

Once we know how to separate components by setting boundaries, we can organize these components into layers. Layers are concentric and represent how fundamental (or high-level) components are. At the core, we have the high-level policies, i.e. stable and abstract components encapsulating our business rules. On the outer ring, we have the details, for example, unstable and concrete GUI’s.

Source-level dependencies should be organized according to the dependency rule: outer layers should depend on inner layers (at the source-level), and not vice versa. We can remove violations of the dependency rule by setting boundaries as explained above.

We can identify four main layers, although the number may vary:

- Entities: objects containing critical business logic. For example, a bank could establish that no loans are granted to customers not satisfying some credit score requirements. Entities may be shared across apps in the same enterprise.

- Use-cases: app-specific business rules. For example, the sequence of screens to execute a bank transfer.

- Interface adapters: Gateways, presenters and controllers. For example, this layer will contain the MVC architecture of the GUI and also objects that transform data between the format of the database and the use-cases.

- Frameworks and drivers: web frameworks, database, the view of MVC.

Only simple data structures are allowed to cross the layer boundaries. These are simple data structures, convenient for the inner layer. Examples are ViewModels and DTOs.

Finally, since the outer layer is hard to test (think views and database), we can use the pattern of humble objects to increase testability. The view, say, becomes “humble” while the presenter does all the formatting work. It provides the view with simple strings and boolean flags that the view displays in the UI. In particular, the view doesn’t perform any work like formatting a table of numbers or deciding if the color of a loss balance should be different. In this way, the tests can be written easily against the presenter.

To read more about layers a good starting point is Uncle Bob’s original post. Another is, of course, the Clean architecture book itself.

What’s more in the book

Clean architecture contains many more topics and examples I can’t cover here for space reasons.

Some of them are:

- A case study on video sales.

- A simplified design of the game hunt the wumpus.

- An example of service-oriented architecture.

- A “tension diagram” for components principles.

- Structured programming, OOP and functional programming vs architecture.

- Why databases, frameworks and the web are details.

- Packages by layer vs packages by feature.

- Some examples of what the main component should do and look like.

- A chapter on clean embedded architecture.

- A brief description of SOLID principles.

- A chapter on historical architecture of systems from the 60’s onwards.

Let me know in the comments if you want any topic covered on my blog.

My opinion and review

Clean architecture gives solid advice to make code flexible and maintainable. Its applications of the dependency inversion principle are deep and interesting and will make you understand how to use polymorphism to de-couple software. The book is easy to read but sometimes redundant, so I would suggest you skim over the parts you already know.

Some of the pros are:

- A clear metric to monitor components quality over time (distance from the “main sequence”). Let me know in the comments if you know of any tool for integrating this check in a continuous integration pipeline.

- Clear component-level principles, not only lower-level principles (i.e. class-level) or higher-level principles (i.e. architecture) as other books.

- Good examples of the dependency inversion principle and how to use it to make software flexible.

- Make frameworks and databases secondary to the main purpose of software.

- Historical chapters are fun.

Some of the cons are:

- If you follow Uncle Bob, some parts are already treated elsewhere, e.g. SOLID principles.

- In addition to the above, the book could be shorter. For example, the chapters about programming paradigms are interesting but could have been a shorter appendix.

- Deeper and more case studies and examples would have been nice.

So what do you think about Clean architecture? Let me know in the comments.